Follow up on cracking ZIP archives in Rust

In a previous article, we explored how to build - step by step - a CLI in Rust to brute-force protected ZIP archives.

The outcome of this research was the creation of the project zip-password-finder.

Since the last publication, the project has been slowly evolving to mitigate the shortcomings that were highlighted.

In this follow-up entry we will go over the improvements made and the latest performance numbers.

A short recap

The project zip-password-finder supports two different modes to find the password: either from a dictionary file or by generating candidates from a charset.

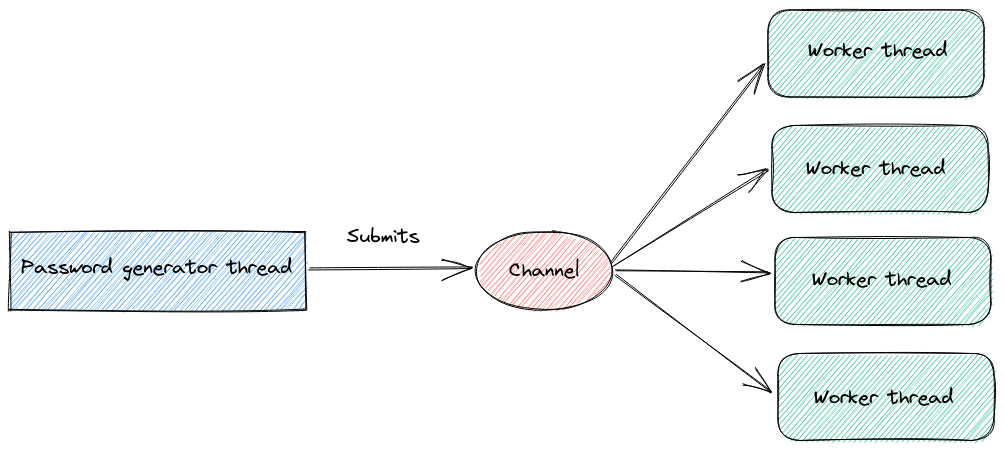

It uses a channel-based architecture to distribute candidate passwords to a set of workers who are responsible for testing them in parallel.

It is important to mention that ZIP archives can be encrypted using either ZipCrypto or AES.

In practice, ZipCrypto can be attacked and is much cheaper to brute force.

As it can still be found in the wild, most notably produced by Windows machines, zip-password-finder handles this format transparently for the user.

However, we won't give it much thought in this article given its issues and our desire to focus on the more difficult AES case.

Test drive

Here is the CLI we are going to work with.

./zip-password-finder -h

Find the password of protected ZIP files

Usage: zip-password-finder [OPTIONS] --inputFile <inputFile>

Options:

-i, --inputFile <inputFile>

path to zip input file

-w, --workers <workers>

number of workers

-p, --passwordDictionary <passwordDictionary>

path to a password dictionary file

-c, --charset <charset>

charset to use to generate password [default: medium] [possible values: basic, easy, medium, hard]

--minPasswordLen <minPasswordLen>

minimum password length [default: 1]

--maxPasswordLen <maxPasswordLen>

maximum password length [default: 10]

-h, --help

Print help information

-V, --version

Print version information

We can give it a try by creating an encrypted zip archive; let's call it secret.zip with the four-characters password "ab12".

zipinfo secret.zip

Archive: secret.zip

Zip file size: 209 bytes, number of entries: 1

-rw-rw-r-- 6.3 unx 13 Bx u099 23-Mar-27 20:17 secret.txt

1 file, 13 bytes uncompressed, 21 bytes compressed: -61.5%

Given that the password is pretty short, we can ask zip-password-finder to generate all possible passwords from the charset formed by the lowercase letters, uppercase letters, and digits (called medium).

time ./zip-password-finder -i test-encrypted.zip --charset medium

It returns with the right answer shortly before the one-minute mark.

time ./zip-password-finder-0.2 -i ~/Workspace/blog-data/find-password-zip/secret.zip -c medium

Using 4 workers to test passwords

Generating passwords with length from 1 to 10 for charset with length 62

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z', 'A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'I', 'J', 'K', 'L', 'M', 'N', 'O', 'P', 'Q', 'R', 'S', 'T', 'U', 'V', 'W', 'X', 'Y', 'Z', '0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9']

Starting search space for password length 1 (62 possibilities)

Starting search space for password length 2 (3844 possibilities) (61 passwords generated so far)

Starting search space for password length 3 (238328 possibilities) (3905 passwords generated so far)

Starting search space for password length 4 (14776336 possibilities) (242233 passwords generated so far)

Password found 'ab12'

real 0m54,262s

user 3m40,620s

sys 0m2,431s

Finding a 4-letters password on such a small charset was a rather easy task for a modern CPU.

There are only (26 lower + 26 upper + 10 digit)^4 = 14.776.336 candidates to test.

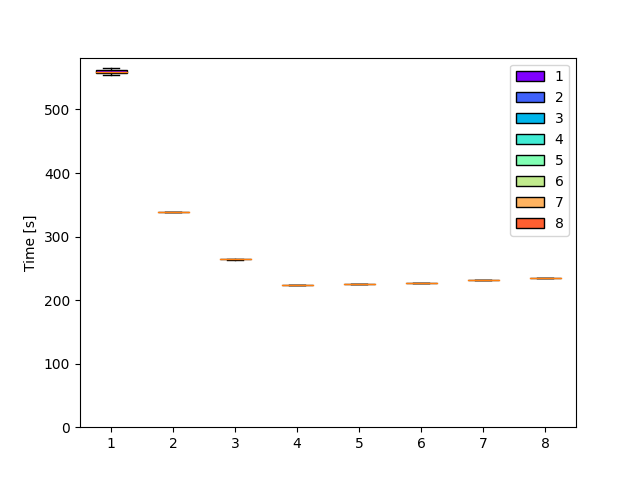

However, a learning from the previous article is that scalability suffers as the number of workers increases.

Improving on this limitation is critical for being able to work against real-world passwords.

We will reuse this test file for the benchmarks in the rest of the article.

Independent workers

Previous measurements clearly showed that performance did not improve linearly with the number of workers.

We previously attributed the flat line between 4 and 8 workers to the Hyperthreading on my CPU, which does not bode well for this type of workload.

The most logical hypothesis is that there is a source of contention in the current architecture as the number of workers increases.

It seems straightforward to believe that workers are somehow competing and synchronizing with each other to poll candidates from the channel.

Picking an easy architecture helped us get started at the beginning, but it could very well be a limiting factor to get faster.

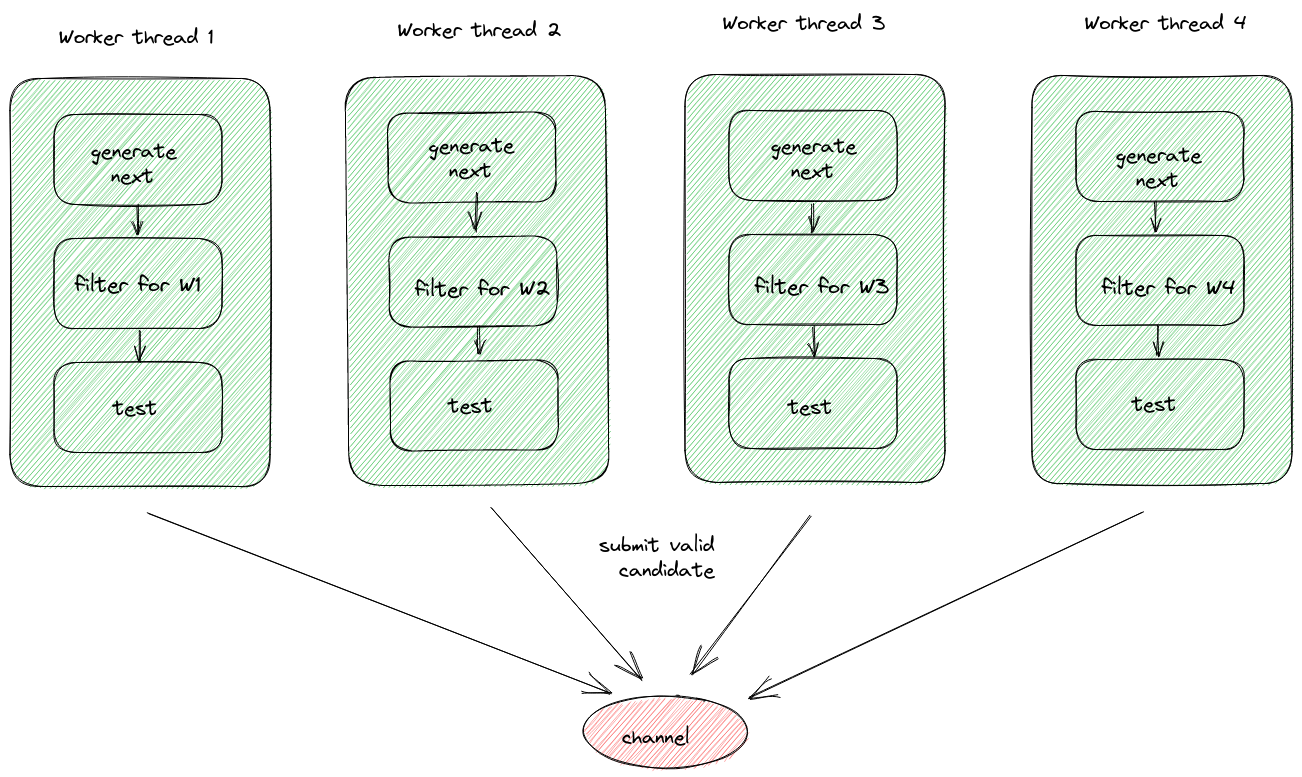

An interesting insight is that workers do not need to share the same source of passwords.

Each worker could agree upfront to work on a subset of the generated passwords.

Given n workers, each worker generates and tests 1/n of the passwords with an offset.

For instance, with 3 workers on a lowercase charset:

- first worker : "a", "d", "g", "j", ...

- second worker: "b", "e", "h", "k", ...

- third worker : "c", "f", "i", "l", ...

This way, we remove all coordination at runtime, so the workers can make progress in isolation.

This pattern can be elegantly integrated by refactoring the dictionary reader and password generator to be proper Iterator.

let mut passwords_iter: Box<dyn Iterator<Item = String>> = match strategy {

Strategy::GenPasswords {

charset,

min_password_len,

max_password_len,

} => {

let iterator = password_generator_iter(&charset, min_password_len, max_password_len);

Box::new(iterator)

},

Strategy::PasswordFile(dictionary_path) => {

let iterator = password_dictionary_reader_iter(&dictionary_path);

Box::new(iterator)

}

};

// filtering iterator for worker `worker_index`

passwords_iter = if worker_count > 1 {

let filtered = passwords_iter.enumerate().filter_map(move |(i, candidate)| {

if i % worker_count == worker_index - 1 {

Some(candidate)

} else {

None

}

})

Box::new(filtered)

} else {

passwords_iter

}

// processing loop

for password in passwords_iter {

...

}

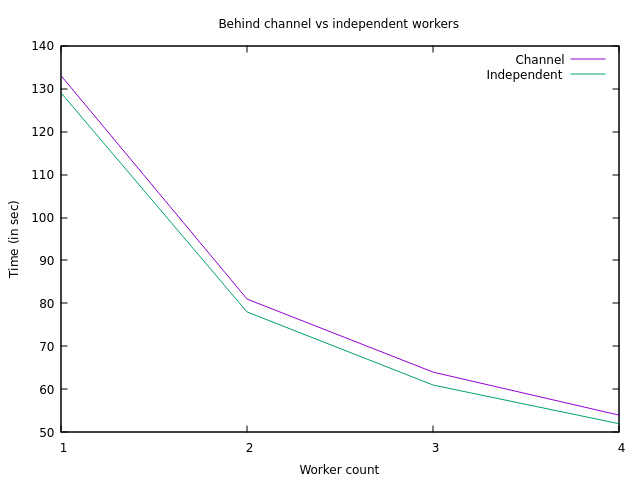

Benchmarking both architectures on the secret.zip archive with various numbers of workers yields the following result.

The performance improved slightly, but the shape of the curve did not change, meaning the scalability profile did not get any better.

Switching to independent workers is beneficial, but it did not have the desired effect.

There is more research to be done to improve scalability.

Cheaper iteration

One obvious strategy to go faster is to make testing a candidate as cheap as possible.

The first version of the project was rather naive in that regard.

let mut archive = zip::ZipArchive::new(file).expect("Archive validated before-hand");

loop {

match receive_password.recv() {

Err(_) => break, // channel disconnected, stop thread

Ok(password) => {

let res = archive.by_index_decrypt(0, password.as_bytes()); // decrypt first file in archive

match res {

Err(e) => panic!("Unexpected error {:?}", e),

Ok(Err(_)) => (), // invalid password - continue

Ok(Ok(_)) => {

println!("Password found:{}", password);

break; // stop thread

}

}

}

}

}

For each candidate, the function archive.by_index_decrypt(0, password) is called; hopefully it does not do too much.

This function belongs to the zip-rs project and performs the following actions:

- Find file data in the archive based on file index used (here 0).

- Verify that the file is encrypted.

- Load raw content of the file.

- Prepare AES decoder (get salt & verification key).

- Compute key for candidate and salt.

- Compare derived key to verification key.

Well, that is a lot of repetition!

Ideally, we just want to perform the 5th and 6th steps for each candidate, the rest can be pre-computed.

To do this, I had to fork the zip-rs crate to expose some internals.

On the AesReader:

/// Read the AES header bytes and returns the key and salt.

///

/// # Returns

///

/// the key and the salt

pub fn get_key_and_salt(mut self) -> io::Result<(Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>)> {

let salt_length = self.aes_mode.salt_length();

let mut salt = vec![0; salt_length];

self.reader.read_exact(&mut salt)?;

// next are 2 bytes used for password verification

let mut pwd_verification_value = vec![0; PWD_VERIFY_LENGTH];

self.reader.read_exact(&mut pwd_verification_value)?;

Ok((pwd_verification_value, salt))

}

And on the ZipArchiveReader:

/// Returns key and salt

pub fn get_aes_key_and_salt(

&mut self,

file_number: usize,

) -> ZipResult<Option<(AesMode, Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>)>> {

let data = self

.shared

.files

.get(file_number)

.ok_or(ZipError::FileNotFound)?;

if !data.encrypted {

return Err(ZipError::UnsupportedArchive(ZipError::PASSWORD_REQUIRED));

}

let limit_reader = find_content(data, &mut self.reader)?;

match data.aes_mode {

None => Ok(None),

Some((aes_mode, _)) => {

let (key, salt) = AesReader::new(limit_reader, aes_mode, data.compressed_size)

.get_key_and_salt() // NEW

.expect("AES reader failed");

Ok(Some((aes_mode, key, salt)))

}

}

}

Luckily, Cargo makes it very low-friction to work with a forked crate!

zip = { git = "https://github.com/agourlay/zip.git", branch = "zip-password-finder" }

Thanks to this insight, it is possible to pre-compute most of the AES information, removing a lot of work from the processing loop.

// AES info bindings initialized once

let mut derived_key_len = ...

let mut derived_key: Vec<u8> = ...

let mut salt: Vec<u8> = ...

let mut key: Vec<u8> = ...

// processing loop

for password in passwords_iter {

let password_bytes = password.as_bytes();

let mut potential_match = true;

// process AES KEY

// use PBKDF2 with HMAC-Sha1 to derive the key

pbkdf2::pbkdf2::<Hmac<Sha1>>(password_bytes, &salt, 1000, &mut derived_key).expect("PBKDF2 should not fail");

let pwd_verify = &derived_key[derived_key_len - 2..];

// the last 2 bytes should equal the password verification value

potential_match = key == pwd_verify;

if potential_match {

// try to decode archive to eliminate collision

let res = archive.by_index_decrypt(0, password.as_bytes()); // decrypt first file in archive

...

}

}

Benchmarking the difference:

hyperfine --runs 2 \

--warmup 1 \

-n before "./zip-password-finder-before -i secret.zip -c medium" \

-n after "./zip-password-finder-after -i secret.zip -c medium"

| Command | Mean [s] | Min [s] | Max [s] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

before | 58.977 ± 0.512 | 58.615 | 59.339 | 1.08 ± 0.01 |

after | 54.476 ± 0.037 | 54.450 | 54.503 | 1.00 |

A solid 8% improvement is something I gladly take.

Performance over time

Outside of the two previously mentioned improvements, the runtime improved slowly over time.

| Command | Mean [s] | Min [s] | Max [s] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0.1 | 62.317 ± 0.224 | 62.159 | 62.475 | 1.21 ± 0.01 |

0.2 | 58.823 ± 0.013 | 58.814 | 58.833 | 1.14 ± 0.01 |

0.3 | 59.423 ± 0.047 | 59.390 | 59.456 | 1.15 ± 0.01 |

0.4 | 55.562 ± 0.034 | 55.538 | 55.586 | 1.08 ± 0.01 |

0.5 | 56.877 ± 0.362 | 56.621 | 57.132 | 1.10 ± 0.01 |

0.5.1 | 54.230 ± 0.424 | 53.930 | 54.530 | 1.05 ± 0.01 |

0.6 | 51.619 ± 0.412 | 51.327 | 51.911 | 1.00 |

0.6.1 | 52.421 ± 0.166 | 52.303 | 52.538 | 1.02 ± 0.01 |

0.6.2 | 52.149 ± 0.155 | 52.039 | 52.259 | 1.01 ± 0.01 |

0.6.3 | 52.073 ± 0.193 | 51.937 | 52.209 | 1.01 ± 0.01 |

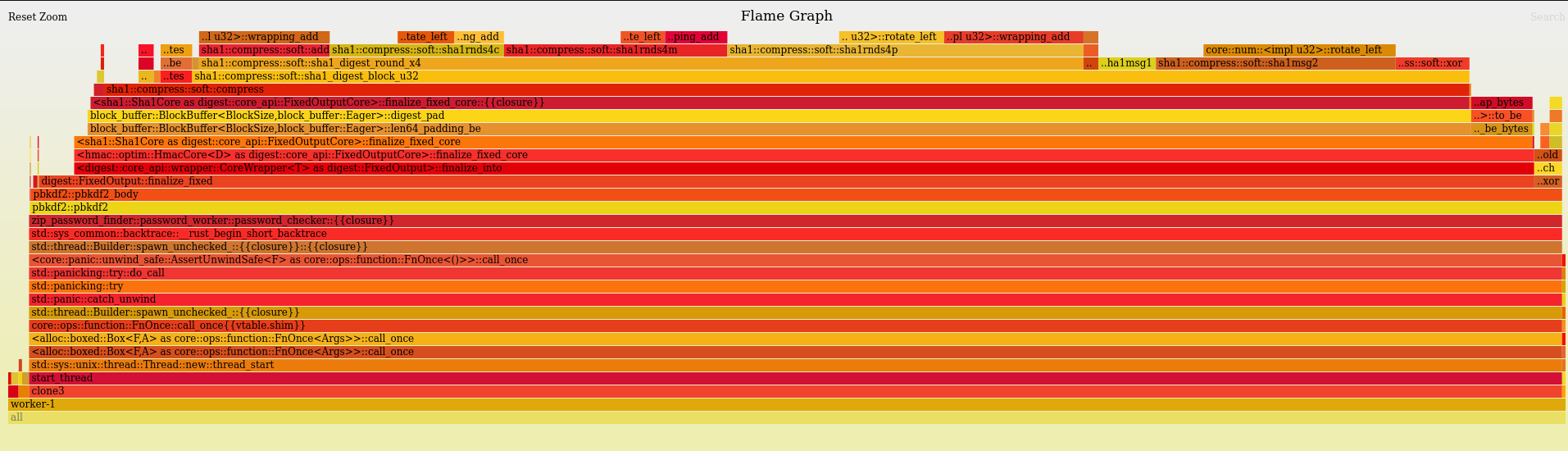

However, the performance optimizations are hitting a wall; a single bottleneck is now largely dominating the CPU usage.

Each worker is busy doing the following: (full flamegraph available).

Computing the SHA1 for each candidate takes up to 90% of the total CPU time; improving this implementation would have a massive impact on the runtime!

It is interesting to note that function is called sha1::compress::soft::compress - now that's a weird name.

Let's take a look under the hood.

cpufeatures::new!(shani_cpuid, "sha", "sse2", "ssse3", "sse4.1");

pub fn compress(state: &mut [u32; 5], blocks: &[[u8; 64]]) {

if shani_cpuid::get() {

unsafe {

digest_blocks(state, blocks);

}

} else {

super::soft::compress(state, blocks);

}

}

#[target_feature(enable = "sha,sse2,ssse3,sse4.1")]

unsafe fn digest_blocks(state: &mut [u32; 5], blocks: &[[u8; 64]]) {

...

}

This code is picking an implementation at runtime based on the capabilities of the CPU.

The branching depends on the sha, sse2, ssse3 and sse4.1 instruction sets.

Here, soft stands for software, meaning not using hardware acceleration.

But why is my CPU not eligible for the optimized SIMD implementation?

lscpu

Architecture: x86_64

CPU op-mode(s): 32-bit, 64-bit

Address sizes: 39 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

Byte Order: Little Endian

CPU(s): 8

On-line CPU(s) list: 0-7

Vendor ID: GenuineIntel

Model name: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10610U CPU @ 1.80GHz

...

Flags: ...sse sse2 ssse3 sse4_1 sse4_2...

Sadly, I have all the necessary sse instructions but missing the sha one.

This means we need to make sure to use a CPU with SHA instructions to get the best performance.

Optimizing build

Given that I do not have access to adequate hardware, all I can do for the time being is tweak my build in order to squeeze out one last performance gain.

The first idea is to enable Link-time Optimization (LTO), which is an optimization taking place at compile time.

Be aware that it can make the compilation much slower!

There are two possible values for it:

[profile.release]

lto = "thin" or "fat"

A second idea is to a build binary with the best instructions for the current CPU.

RUSTFLAGS="-C target-cpu=native" cargo build --release

Benchmarking those configurations yields the following results:

| Command | Mean [s] | Min [s] | Max [s] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

native | 52.456 ± 2.987 | 50.344 | 54.568 | 1.00 |

master | 57.439 ± 1.135 | 56.637 | 58.241 | 1.09 ± 0.07 |

native-lto | 59.161 ± 0.437 | 58.852 | 59.470 | 1.13 ± 0.06 |

lto-thin | 61.677 ± 0.153 | 61.569 | 61.786 | 1.18 ± 0.07 |

lto-fat | 67.777 ± 0.277 | 67.582 | 67.973 | 1.29 ± 0.07 |

Well, we better not enable LTO but there is a case to be made for a native build.

This performance related section was a bit messy, but we learned a few important things:

- Do not blindly enable LTO without validating that it is beneficial.

- If you are super serious about performance, you would probably benefit from producing native binaries for your hardware.

- Some libraries have alternate implementations depending on the hardware capabilities.

State of the art

To appreciate the performance of zip-password-finder, I thought it would be a good idea to compare it to the state of the art of ZIP cracking.

It seems serious people are using the Hashcat project, which is apparently the "World's fastest password cracker"!

sudo apt-get install hashcat

This tool runs on GPUs; in my case, I had to install the OpenCL Runtime for Intel Core.

It supports a very large list of algorithms, including the one we need here, WinZip.

In order to use Hashcat, we first need to extract the underlying hash of our zip file into a format that is understood by Hashcat.

To that end, we will use zip2john from the John the Ripper project.

Installing it manually with:

git clone https://github.com/openwall/john -b bleeding-jumbo john

cd john/src/

./configure

make -s clean && make -sj4

and then running it

cd /Workspace/john/run

./zip2john ~/zip-files/secret.zip

yields the text

secret.zip/secret.txt:$zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a99031db50f79a*d9e156b830df03899575*$/zip2$:secret.txt:secret.zip:/home/agourlay/zip-files/secret.zip

The output needs to be cleaned up and saved into into a file, hash.txt here.

$zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a99031db50f79a*d9e156b830df03899575*$/zip2$

After a rather tedious setup, it is finally time to crack our hash!

We need to instruct hashcat to:

- perform a brute force attack

- target the

hash.txt - use an algorithm for ZIP archive hashes

- generate passwords for a charset with lower case, upper case and digits (up to 4 chars)

Luckily for us, the help prompt is truly excellent!

Here are the interesting excerpts:

For the attack mode:

- [ Attack Modes ] -

# | Mode

===+======

0 | Straight

1 | Combination

3 | Brute-force

6 | Hybrid Wordlist + Mask

7 | Hybrid Mask + Wordlist

9 | Association

For the hash type:

- [ Hash modes ] -

# | Name | Category

13600 | WinZip | Archive

For the charset:

? | Charset

===+=========

l | abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz [a-z]

u | ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ [A-Z]

d | 0123456789 [0-9]

h | 0123456789abcdef [0-9a-f]

H | 0123456789ABCDEF [0-9A-F]

s | !"#$%&'()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\]^_`{|}~

a | ?l?u?d?s

b | 0x00 - 0xff

According to the documentation, it seems we need to setup a four-characters mask that will be explored incrementally.

After a bit of trial and error, it gives the following magic incantation:

hashcat -a 3 hash.txt -m 13600 -1 ?l?u?d ?1?1?1?1 --increment

Let's go!

time hashcat -a 3 hash.txt -m 13600 -1 ?l?u?d ?1?1?1?1 --increment

hashcat (v6.2.5) starting

OpenCL API (OpenCL 3.0 ) - Platform #1 [Intel(R) Corporation]

=============================================================

* Device #1: Intel(R) UHD Graphics [0x9b41], 12640/25384 MB (2047 MB allocatable), 24MCU

Minimum password length supported by kernel: 0

Maximum password length supported by kernel: 256

Hashes: 1 digests; 1 unique digests, 1 unique salts

Bitmaps: 16 bits, 65536 entries, 0x0000ffff mask, 262144 bytes, 5/13 rotates

Optimizers applied:

* Zero-Byte

* Single-Hash

* Single-Salt

* Brute-Force

* Slow-Hash-SIMD-LOOP

Watchdog: Hardware monitoring interface not found on your system.

Watchdog: Temperature abort trigger disabled.

Host memory required for this attack: 1475 MB

The wordlist or mask that you are using is too small.

This means that hashcat cannot use the full parallel power of your device(s).

Unless you supply more work, your cracking speed will drop.

For tips on supplying more work, see: https://hashcat.net/faq/morework

Approaching final keyspace - workload adjusted.

Session..........: hashcat

Status...........: Exhausted

Hash.Mode........: 13600 (WinZip)

Hash.Target......: $zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a9.../zip2$

Time.Started.....: Sat Apr 1 15:53:49 2023 (0 secs)

Time.Estimated...: Sat Apr 1 15:53:49 2023 (0 secs)

Kernel.Feature...: Pure Kernel

Guess.Mask.......: ?1 [1]

Guess.Charset....: -1 ?l?u?d, -2 Undefined, -3 Undefined, -4 Undefined

Guess.Queue......: 1/4 (25.00%)

Speed.#1.........: 117 H/s (6.27ms) @ Accel:32 Loops:999 Thr:8 Vec:1

Recovered........: 0/1 (0.00%) Digests

Progress.........: 62/62 (100.00%)

Rejected.........: 0/62 (0.00%)

Restore.Point....: 1/1 (100.00%)

Restore.Sub.#1...: Salt:0 Amplifier:61-62 Iteration:0-999

Candidate.Engine.: Device Generator

Candidates.#1....: X -> X

The wordlist or mask that you are using is too small.

This means that hashcat cannot use the full parallel power of your device(s).

Unless you supply more work, your cracking speed will drop.

For tips on supplying more work, see: https://hashcat.net/faq/morework

Approaching final keyspace - workload adjusted.

Session..........: hashcat

Status...........: Exhausted

Hash.Mode........: 13600 (WinZip)

Hash.Target......: $zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a9.../zip2$

Time.Started.....: Sat Apr 1 15:53:52 2023 (0 secs)

Time.Estimated...: Sat Apr 1 15:53:52 2023 (0 secs)

Kernel.Feature...: Pure Kernel

Guess.Mask.......: ?1?1 [2]

Guess.Charset....: -1 ?l?u?d, -2 Undefined, -3 Undefined, -4 Undefined

Guess.Queue......: 2/4 (50.00%)

Speed.#1.........: 7321 H/s (6.27ms) @ Accel:16 Loops:999 Thr:16 Vec:1

Recovered........: 0/1 (0.00%) Digests

Progress.........: 3844/3844 (100.00%)

Rejected.........: 0/3844 (0.00%)

Restore.Point....: 62/62 (100.00%)

Restore.Sub.#1...: Salt:0 Amplifier:61-62 Iteration:0-999

Candidate.Engine.: Device Generator

Candidates.#1....: Xa -> XQ

The wordlist or mask that you are using is too small.

This means that hashcat cannot use the full parallel power of your device(s).

Unless you supply more work, your cracking speed will drop.

For tips on supplying more work, see: https://hashcat.net/faq/morework

Approaching final keyspace - workload adjusted.

Session..........: hashcat

Status...........: Exhausted

Hash.Mode........: 13600 (WinZip)

Hash.Target......: $zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a9.../zip2$

Time.Started.....: Sat Apr 1 15:53:55 2023 (6 secs)

Time.Estimated...: Sat Apr 1 15:54:01 2023 (0 secs)

Kernel.Feature...: Pure Kernel

Guess.Mask.......: ?1?1?1 [3]

Guess.Charset....: -1 ?l?u?d, -2 Undefined, -3 Undefined, -4 Undefined

Guess.Queue......: 3/4 (75.00%)

Speed.#1.........: 40570 H/s (8.17ms) @ Accel:16 Loops:999 Thr:16 Vec:1

Recovered........: 0/1 (0.00%) Digests

Progress.........: 238328/238328 (100.00%)

Rejected.........: 0/238328 (0.00%)

Restore.Point....: 3844/3844 (100.00%)

Restore.Sub.#1...: Salt:0 Amplifier:61-62 Iteration:0-999

Candidate.Engine.: Device Generator

Candidates.#1....: XFz -> XQz

$zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a99031db50f79a*d9e156b830df03899575*$/zip2$:ab12

Session..........: hashcat

Status...........: Cracked

Hash.Mode........: 13600 (WinZip)

Hash.Target......: $zip2$*0*1*0*abf015b7750c67f9*f8fe*d*c97f48465ca6a9.../zip2$

Time.Started.....: Sat Apr 1 15:54:04 2023 (1 sec)

Time.Estimated...: Sat Apr 1 15:54:05 2023 (0 secs)

Kernel.Feature...: Pure Kernel

Guess.Mask.......: ?1?1?1?1 [4]

Guess.Charset....: -1 ?l?u?d, -2 Undefined, -3 Undefined, -4 Undefined

Guess.Queue......: 4/4 (100.00%)

Speed.#1.........: 49139 H/s (101.71ms) @ Accel:16 Loops:999 Thr:16 Vec:1

Recovered........: 1/1 (100.00%) Digests

Progress.........: 36864/14776336 (0.25%)

Rejected.........: 0/36864 (0.00%)

Restore.Point....: 0/238328 (0.00%)

Restore.Sub.#1...: Salt:0 Amplifier:5-6 Iteration:0-999

Candidate.Engine.: Device Generator

Candidates.#1....: aari -> arIS

Started: Sat Apr 1 15:53:42 2023

Stopped: Sat Apr 1 15:54:05 2023

real 0m23,617s

user 0m6,331s

sys 0m10,747s

That's a lot of logs; each bloc represents the outcome of the exploration of length-value space.

In any case, it found the password in 23 seconds, two times faster than zip-password-finder!

At peak speed, it processed 49139 H/s which is roughly 10 times faster than zip-password-finder on my configuration.

It does so while still complaining about not being able to fully use the system.

For this reason, I expect the difference between the two tools to be much larger with a larger password.

Especially if you have a real graphics card, the throughput will likely be expressed in MH.

Hashcat is a fantastic tool with great performance; it was however not easy to setup, so it may be reserved for advanced users.

Future work

The re-architecturing has not solved the scaling issues; it would be interesting to dig deeper and benchmark the code on a machine with a much larger number of cores.

Talking about testing different hardware, it would be great to have results using a CPU with the sha instruction to benefit from proper hardware acceleration.

Being able to speed up the default implementation of the sha1 crate would also yield significant gains.

A current issue is the accumulation of technical debt; by contributing the AES info extraction helpers upstream to the zip-rs, we would avoid having to maintain a fork forever.

Finally, Hashcat has made a great impression, and I would like to explore it for further inspiration.

Conclusion

This article has explained a few performance optimizations that helped making zip-password-finder a bit faster over time.

However, it has also highlighted that the recent efforts have entered a zone of diminishing returns due to a clear bottleneck.

It seems cracking hashes requires dedicated hardware: be it CPUs with particular instructions or even better GPUs.

This has been made somewhat clear by comparing our Rust program to the great Hashcat.

In general, expert tooling tends to perform very well but suffers from an accessibility issue.

The project zip-password-finder is very easy to use but has a long way to go to be competitive.